· Systems Thinking · 3 min read

The Traffic Jam in Your Data Center: A Lesson in Induced Demand

Adding servers to compensate for inefficiency is like buying a bigger fridge because it’s full of spoiled food. Why horizontal scaling creates the exact same problems as 26-lane highways.

Every time a city runs into traffic congestion, the proposed fix is almost insultingly simple:

Add lanes.

More lanes mean more capacity. More capacity means less traffic. Problem solved.

Except… it never is.

Within months, the brand‑new highway fills up again. Commute times creep back to where they were. Everyone is still stuck — just with a wider horizon and a better excuse for why this time it should have worked.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the exact same logic quietly haunts our data centers.

Latency is high? Add servers. Systems are slow? Scale horizontally. Costs exploding? Well… that’s tomorrow’s problem.

Asphalt Optimism

Let’s start with a classic.

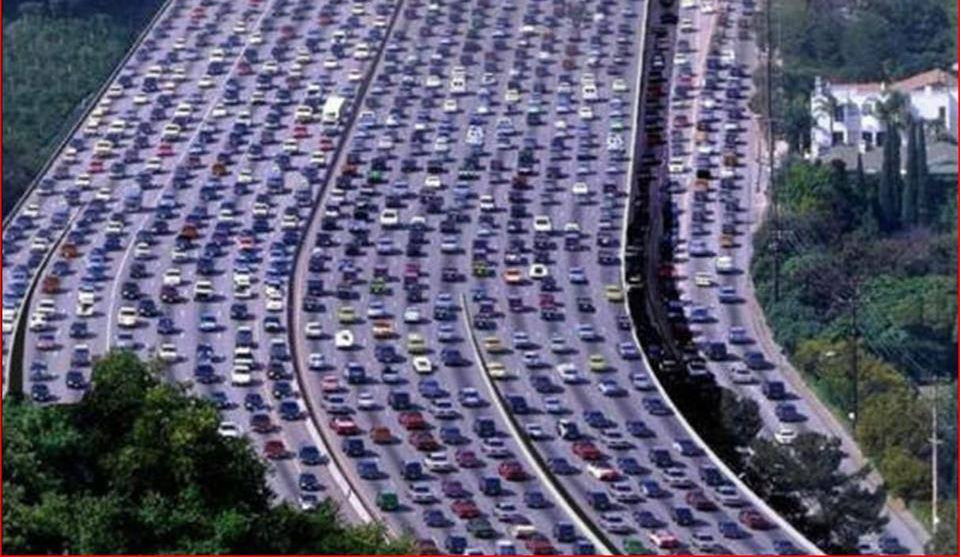

In 2011, Houston unveiled the Katy Freeway — at the time, the widest highway on Earth. Twenty‑six lanes of concrete optimism, delivered for a modest $2.8 billion.

The expectation was obvious: traffic would ease. The outcome was less poetic.

Commute times increased. People drove more. Developers pushed housing farther out. Traffic rebounded faster than anyone had predicted. The system happily absorbed the new capacity and asked for seconds.

Houston didn’t get speed. It got validation that adding lanes mostly adds cars.

When the System Fully Commits

If Houston was subtle, China’s National Highway 110 was not.

In August 2010, a roughly 50‑lane stretch outside Beijing collapsed into a traffic jam stretching nearly 100 kilometers. Movement slowed to about one kilometer per day. Drivers slept in their cars. Vendors appeared, selling bottled water at fifteen times the normal price.

A man‑made circulatory system choked on its own expansion.

No accident. No natural disaster. Just demand responding exactly as systems theory says it will.

Induced Demand, Everywhere

Traffic makes the concept easy to visualize, but the phenomenon is far broader.

Add supply and you don’t relieve pressure — you attract more of it.

Highways invite driving. Parking invites cars. Parking lots replace neighborhoods. (Hello, historic satellite images of downtown Detroit — improving lately, to be fair.)

And in software, compute capacity invites consumption.

Give a team more CPU headroom and it will be filled. Heavier frameworks. More verbose logging. “Temporary” redundancy that somehow survives three re‑architectures.

Each optimization invites new complexity. Each layer adds coordination costs. Before long, the bottleneck isn’t capacity at all.

It’s flow.

When Scaling Makes Things Worse

Networks learned this lesson the hard way.

In 1990, AT&T experienced a long‑distance outage where calls were rerouted into regions marked as “healthy.” Those regions promptly overloaded and failed as well, triggering a cascade that spread faster than the original problem.

The rerouting logic wasn’t malicious. It was well‑intentioned. It was also blind to induced demand.

(I unpack this incident and the cascading failure mechanism in more detail in The Fuckup Almanac.)

Stop Widening the Highway

The practical takeaway is annoyingly unglamorous:

Stop adding lanes.

Instead:

- Prefer smarter caching and back‑pressure over fatter clusters.

- Fix queueing, retries, and fallbacks before buying more nodes.

- Kill features that don’t earn their keep. Fewer cars on the road beat wider roads.

Because if you keep adding capacity to fix bad design, you don’t get speed. You get a parking lot.

Adding servers to compensate for inefficiency is like buying a bigger fridge because it’s full of spoiled food. You don’t need more space.

You need better habits.

(Yes, Volume 1 covers the AT&T outage and other delightful system collapses caused by good intentions.)