· Systems · 9 min read

Digital Ghosts: The Long, Cynical History of Data Protection

We think we invented data protection in the age of CPUs. We didn't. We just gave fancy names to tricks used by 17th-century mapmakers and paranoid monks.

I’ve spent the last few weeks digging into the mechanics of protecting proprietary datasets. It’s a rabbit hole I didn’t plan to fall into, but once you start looking at how we try to stop the world from scraping everything that isn’t physically welded to the floor, you realize we are essentially archeologists pretending to be high-tech engineers.

Fair warning: this post is long. And yet, it’s merely the introduction to a larger series. The sheer volume of what follows should give you an idea of just how deep this hole actually goes. I also apologize in advance for the barrage of examples; I’ve picked only the most fascinating ones to keep things moving, and trust me, I’ve barely scratched the surface of the industry’s shared paranoia.

Most people suffer from a severe case of technocentrism. We like to believe that piracy, data theft, and unauthorized copying are unique challenges of the silicon age—born from some magical property of bits and bytes.

Spoiler alert: They aren’t. We’ve just changed the gear.

The Economics of Ctrl+C

For most of human history, the best “DRM” (Digital Rights Management) wasn’t code; it was physics and a miserable salary.

If a monk in a medieval scriptorium wanted to “pirate” a manuscript, he had to sit on a wooden stool for six months and manually copy it word for word. Physicality was the only firewall we needed. The cost of reproduction was nearly equal to the cost of production, which is a fancy way of saying that “sharing” knowledge back then was a logistical nightmare involving a lot of ink and very little sleep.

The digital revolution didn’t change the nature of theft; it just destroyed the economics of it. When the cost of Ctrl+C dropped to zero, the entire industry had a collective panic attack. And that panic is where the “Modern Status Quo” was born.

The Modern Status Quo (Or: How to Over-Engineer Paranoia)

When we talk about protecting data today, we use high-sounding terms to describe simple, often blunt, logical tricks designed to catch a thief after they’ve already left the building.

- Digital Watermarking (The LSB Trick): We hide ownership signals in the noise. One of the most common methods is LSB (Least Significant Bit) steganography. In an image, for example, we slightly alter the very last bit of a pixel’s color value. To a human, the difference between a pixel value of 254 and 255 is invisible. To a machine, it’s a digital whisper saying “This belongs to Adam Korga.” It’s basically whispering into a hurricane and hoping someone is listening with a very expensive microphone.

- Fingerprinting: This is “Traitor Tracing.” You don’t give everyone the same dataset. You give them slightly different versions—perhaps different intentional typos or subtle variations in numerical data. If the data leaks, you don’t just know it was stolen; you know exactly which “trusted partner” decided to sell you out.

- Honeytokens (Nihilartikel): Inserting fake records into a database. If your competitor’s automated scraper suddenly starts sending “Urgent Marketing” emails to a fake entry like John Doe living at FakeStreet 404, the system screams. It’s a digital tripwire for people who are too lazy to verify their loot.

- Proof of Existence: Using cryptographic hashes—the technical backbone of the ever-hyped Blockchain—to timestamp a dataset. It doesn’t stop the theft, but it allows you to walk into a courtroom and prove you had this exact sequence of bytes three years before the defendant “innovated” it.

Historical Plagiarism: The OG Trap Streets

If you look past the code, you’ll find that these are just digital ghosts of analog survival tactics.

Take the cryptographic hash mentioned above. We treat “Proof of Existence” like a revolutionary digital miracle, but conceptually, it’s just a high-velocity version of ancient notarization. A hash is essentially a wax seal for people who don’t like fire. Ancient civilizations understood that to prove a document hadn’t been tampered with, you needed a public, immutable witness. We just replaced the parchment and the official seal with a decentralized ledger and a carbon footprint the size of a small moon. Same logic, same paranoia, just better marketing.

Before computers, certain datasets were worth literal fortunes. Mathematical tables and log charts in the 18th and 19th centuries were the “Big Data” of their time. Back then, “Computers” weren’t machines; they were actual humans—a formal profession performed by tens of thousands of people globally. Various estimates suggest there were between 20,000 and 100,000 such specialists in the first half of the 20th century, crunching numbers by hand until their eyes bled.

Calculating these tables took decades of collective suffering. To protect this investment, publishers would insert intentional, “invisible” errors in the last decimal places.

This worked because of the diminishing returns of precision. To give you a modern perspective: NASA today, in its most critical interplanetary calculations, uses the value of with only 15 or 16 decimal places (the IEEE 754 standard). According to engineers at JPL, just 9 decimal places are enough to calculate the Earth’s circumference with millimeter accuracy. 15 digits is enough to navigate between planets without hitting a moon.

In the 1800s, the logic was the same. If a publisher fudged the 12th decimal place, it made absolutely no difference to a bridge builder. But for a lawyer in a courtroom, it was the “smoking gun.” If the same error appeared in a rival’s table, it was proof of theft, not a coincidental miscalculation.

And then there are the maps and fake identities.

- Agloe, New York: In the 1930s, mapmakers Lindberg and Alpers invented the town of “Agloe” and put it on a map to catch thieves. When it appeared on a Rand McNally map, they thought they had caught a thief—until it turned out the “trap” had become a real general store because people kept driving there looking for the town. The fiction became reality.

- Lillian Mountweazel: The 1975 New Columbia Encyclopedia included a fake entry for Lillian Mountweazel, a fountain designer who supposedly died in an explosion. She was a nihilartikel (Latin for “nothing-article”) designed to catch copycats.

- Jungftak: A fake botanist inserted into the Appleton’s Cyclopædia of American Biography to find out who was lazy enough to copy the entire volume without checking the facts. If Jungftak appeared in your “original research,” you were a Ctrl+C enthusiast long before the command existed.

Active Traps: Analog IDS

Before we had digital “Honeytokens,” the publishers of the Yellow Pages were running a very effective analog Intruder Detection System (IDS).

To their massive databases, they added entries for fictional companies with phone numbers that led directly to the publisher’s security office. If that phone rang and a telemarketer asked for a non-existent business, the publisher had a “smoking gun” that their database had been stolen.

It was a perfect, low-tech logic gate. Until the legal system stepped in.

In the case Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. (1991), the US Supreme Court ruled that a phone book—as a collection of facts—doesn’t meet the “originality” requirement for copyright protection. It didn’t matter how many traps you set; facts are facts, and they belong to everyone. This is a ghost that still haunts us today in every debate about AI training data.

The Canary in the High-Stakes Coal Mine

Where the stakes were high enough—in politics or military intelligence—we used fingerprinting long before it was automated.

One famous variant is the Canary Trap, popularized by Tom Clancy. To catch a leaker in a boardroom, you vary the data: one member sees a loss of 1.52 million, a third sees “one and a half million” written in words. When the number appears in the paper, the canary has sung, and you know exactly which cage it came from.

British intelligence (MI5/MI6) used the Barium Meal Test. Like a doctor uses barium to see a digestive tract on an X-ray, spies “feed” a suspect a unique piece of intelligence. If that specific “meal” shows up in enemy hands, the source is undeniable.

Hardware Signatures: The Typewriter’s DNA

Even the “logs” we rely on today had analog predecessors. Typewriter Fingerprinting—the forensic analysis of microscopic flaws in a machine’s typeface—was a precise science long before pop culture (like G.I. Jane) simplified it. Each typewriter had a unique “signature” born from the wear and tear of its keys.

Today, this has evolved into the Machine Identification Code (MIC)—those nearly invisible yellow dots on color laser prints that encode the printer’s serial number and timestamp. Even if you bypass the software, the physical paper still carries the machine’s identity.

Access Models: The Library as a Server

Finally, there’s the question of how we access data. Modern SaaS models rely on APIs and Rate-Limiting to prevent scraping. The idea is to separate the data contract from the storage, ensuring the user only sees what they are authorized to see—and only as fast as we allow.

Unsurprisingly, this is also an old trick.

Enter the Libri Catenati—the chained libraries of the Middle Ages. This was the physical implementation of DRM. The library was the Server, and the librarian was the API Gateway, authenticating the “user” before granting access to a specific volume.

The fact that the book was literally chained to the desk meant you had a Streaming Only model; you couldn’t “download” the data. The physical limitations—the time it took to manually copy a page—acted as a natural Rate Limiting system, preventing mass “scraping” of knowledge by anyone without a lot of patience and very steady hands.

The Tip of the Iceberg

Phew. I think that’s enough for today.

My goal with this text was simply to signal the fact that this arms race—this constant cycle of locking things down only to have them scraped, copied, and repurposed—is far older than many people in the “next-gen” security industry would like to admit.

We’ve barely scratched the surface of cybersecurity here. We’ve talked about the traps, but we haven’t touched the actual battlefield. In the coming weeks, we’re going to pivot toward even weirder territory: the philosophical and legal definitions of “intellectual property,” “authorship,” and what it even means to be “creative” in an era where the assembly line is fully automated.

It might feel like a detour, but stay with me. This entire series is technical at its core. We’re just building the context we need so that when we finally connect all these dots back to the current mess surrounding Generative AI, you’ll see the system for what it actually is.

Be patient. 😀

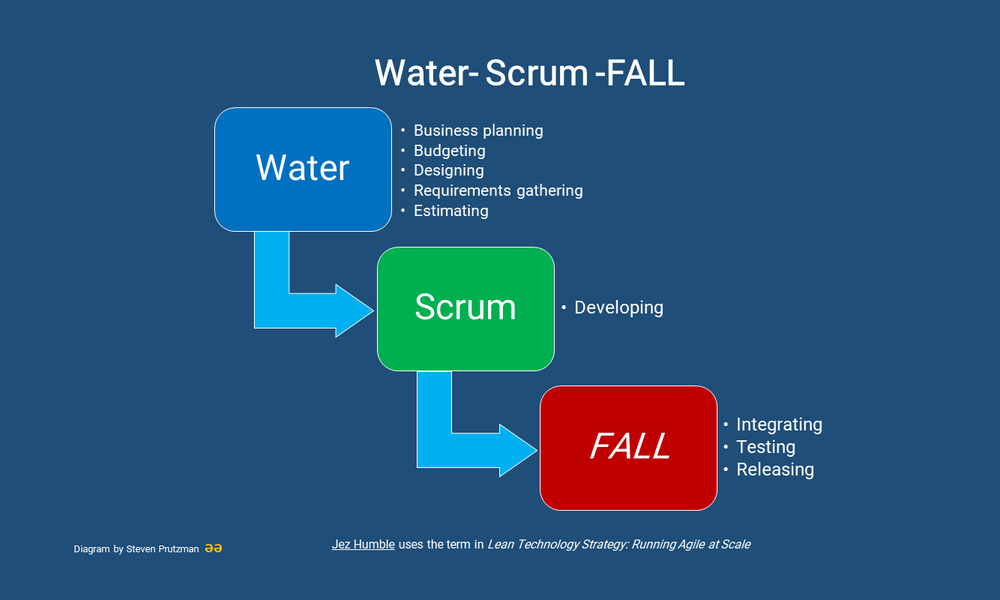

Modern Data Protection Techniques

Academic and technical foundations of digital watermarking, fingerprinting, and honeytokens.

4 sources

Modern Data Protection Techniques

Academic and technical foundations of digital watermarking, fingerprinting, and honeytokens.

- Digital Watermarking and SteganographyCox, I. J., Miller, M. L., Bloom, J. A., Fridrich, J., & Kalker, T. 2007

Foundational textbook on the mathematical basis of watermarking.

- Collusion-secure fingerprinting for digital dataIEEE Transactions on Information Theory Boneh, D., & Shaw, J. 1998

Key theoretical work on the mathematics of fingerprinting.

- Honeypots: Tracking HackersSpitzner, L. 2003

A classic text on IT traps and deception.

- How to time-stamp a digital documentJournal of Cryptology Haber, S., & Stornetta, W. S. 1991

The foundational work that paved the way for Blockchain technology.

Analog Predecessors & Historical Context

The historical roots of data protection, from map-making to human computers.

6 sources

Analog Predecessors & Historical Context

The historical roots of data protection, from map-making to human computers.

- When Computers Were HumanGrier, D. A. 2005

The definitive history of the 'computer' profession before the digital era.

- How Many Decimals of Pi Do We Really Need?NASA/JPL Edu News Rayman, M. 2022

Source for precision standards in space engineering.

- How to Lie with MapsMonmonier, M. 1996

A deep dive into cartographic traps and manipulations.

- Not a WordThe New Yorker Alford, H. 2005

An essay describing the Mountweazel phenomenon and Nihilartikel entries.

- The Chained LibraryStreeter, B. H. 1931

A study of physical DRM and access control in English libraries.

- SpycatcherWright, P. 1987

Memoirs of an MI5 officer; source for the Barium Meal Test and Canary Traps.